One of the state’s major teachers’ unions is gearing up for the next legislative session with their eyes on hot-button topics including restoring public employees’ right to strike and ending “the destructive and punitive aspects of the MCAS system.”

The Massachusetts Teachers Association rolled out its five top education and labor priorities for the 2023-2024 session at the State House Thursday afternoon, joined by educators and supportive legislators.

In addition to striking and standardized testing, other initiatives the union plans to pursue include providing more resources for prekindergarten-12 public schools beyond the Student Opportunity Act, investing in public higher education and increasing cost-of-living adjustment in payment to retired educators.

“It’s time now to achieve the right to strike, return what is a human right back to the public sector workers,” said MTA President Max Page.

Deb Gesualdo, president of the Malden Education Association — which went on strike for one day this October after months-long contract negotiations — said going on strike is “not an easy decision” but that it was “an act of love” because “students and educators weren’t safe in their school buildings.”

Striking is illegal in Massachusetts for public school educators because of a state law that stipulates “no public employee or employee organization shall engage in a strike, and no public employee or employee organization shall induce, encourage or condone any strike, work stoppage, slowdown or withholding of services by such public employees.”

This session Reps. Mike Connolly of Cambridge and Erika Uyterhoeven of Somerville joined the ranks of lawmakers who over the years have filed bills to lift the ban on work stoppage for all public employees with a bill (H 1946). The bill accompanied a study order in September for a Committee on Labor and Workforce Development investigation, which was then reported favorably by the committee and most recently discharged to the Committee on House Rules, where it has been since Sept. 6.

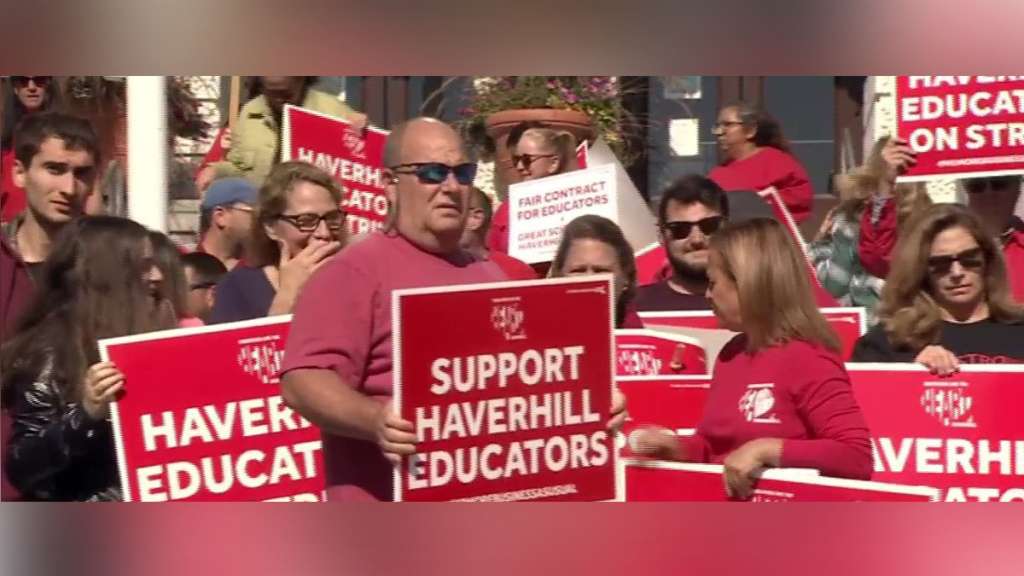

Despite state law, educators in Malden, Brookline and Haverhill went on strike this year.

In Malden, workers were asking for a contract that included higher pay, smaller class sizes and safer school environments, according to WCVB.

“We had to take an illegal action because that illegal action is what was right,” she said. “The right to strike is a human right and the continued prohibition on the right to strike is a continued prohibition on every single blessed public sector worker’s right to free speech, we shouldn’t have less rights than any other worker in the Commonwealth.”

After six months of negotiations, the union met with the school committee for a total 16 hours over two days after the union said they would strike — and did on the second day of negotiations — before both parties came to a tentative agreement, Gesualdo said.

The union president said she believes restoring a right to strike would cause less strikes in schools, as it would give teachers’ unions more leverage in collective bargaining negotiations.

“It’s amazing how quickly things get done when a school committee has to take it seriously. Having a right to strike will not impede bargaining, it will actually help it, and bargaining will progress faster,” she said.

Educators also spoke out Thursday on a long-held policy goal — eliminating the “destructive and punitive aspects of the MCAS exams” and developing more effective practices for assessing public schools.

The measurement and accountability system is “invalid, undemocratic, inequitable,” UMass Lowell associate professor of education and director of research for the Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessment Jack Schneider said, and it “tells us more about student background variables than about what they’re learning in school.”

Some educators have long said the standardized testing exams lead teachers to “teach to the test” instead of educating students on what they believe to be the best curriculum, as well as social emotional skills.

“We don’t teach science, and we don’t teach ELA and we don’t teach math at the elementary level, what we teach is test taking skills,” said MTA vice president and former fifth grade teacher Deb McCarthy.

Schneider also argued Thursday that standardized testing segregates communities and school districts, as wealthier districts tend to do better on the exams. Being rated a “good school” by good MCAS scores drives up property values, he said, and leads already wealthy people to move to places with well-funded school districts and leaves the marginalized behind.

Still, many, including Education Commissioner Jeffrey Riley, say MCAS scores are an important tool to “predict later outcomes in education and earning,” and the state Board of Education voted this summer to raise the minimum score that this year’s incoming freshman class and at least the four classes that follow will have to attain on the English language arts, math, and science and technology/engineering test in order to graduate.

Page said the union is working on turning these priorities into “actionable legislation” in time for the new session which starts in January.

Sen. Pat Jehlen of Somerville, who serves as the chair of the Joint Committee on Labor and Workforce Development, came to the MTA event and said she was moved by educators’ stories of needing a liveable wage and seeing segregation caused by the MCAS assessment.

When asked if she believes if some of the union’s asks could be met by legislators this session she said, “This is a lot, and we don’t have infinite dollars, but I’m hopeful.”

(Copyright (c) 2024 State House News Service.